Minnesota Starvation Experiment: Why dieting makes us fat. The Psychology of Hunger.

One of the first scientific studies on what hunger does to the mind was observed in a study remembered as the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

Milos Pokimica

Written By: Milos Pokimica

Medically Reviewed by: Dr. Xiùying Wáng, M.D.

Updated January 7, 2024Key Takeaways:

– One of the first scientific studies on what hunger does to the mind is remembered as the Minnesota Starvation Experiment performed by the University of Minnesota back in 1944.

– The Minnesota Starvation Experiment was a study where the goal was to live on a diet of 1600 calories for six months. In the first 12 weeks, there was a 3200-calorie control period, and then a real experiment started.

– Men were housed in a basement of the Minnesota University Stadium in windowless rooms with a program of mental and physical exercises. Diet was strictly controlled, and they could not cheat because they were in some sense incarcerated for six months.

– On a calorie restriction of 1600 calories after some initial period, subjects started to lose weight and by the end of the study, they lost a significant number of pounds. – What was additionally important is that the experiment showed significant behavioral changes. Starvation has induced severe psychological effects on subjects.

– After the experiment was over subject rapidly put on weight but not only that. They gained more than what they had at the starting point. Dieting made them fatter. They experienced something called extreme hunger.

– Prolonged food deprivation caused significant changes in body composition, metabolism, and appetite regulation. The men lost an average of 25% of their body weight, mostly from muscle and fat tissue.

– Their basal metabolic rate (the amount of energy they burned at rest) dropped by about 40%.

– Their food intake increased by about 50% during the refeeding phase, but it took them several months to regain their normal weight and body composition.

– Subjects also experienced various physical and mental symptoms, such as fatigue, weakness, dizziness, edema, hair loss, anemia, depression, anxiety, irritability, apathy, obsession with food, and social withdrawal.

– A study found that subjects can lose their identity and their self-controlling mechanisms when forced to be in a state of extreme hunger.

– What was a real discovery was that even when the study was over the fear of starvation never went away.

– The survival mechanism that helps restore muscle mass and prevent further weight loss is called “collateral fattening” and it has to do with the role of muscle mass in regulating hunger–appetite, and weight.

– The amount of muscle and fat that you regain after starvation or dieting is determined by how much fat you had before. The leaner you were, the more fat you will regain, and the longer it will take to recover your muscle mass. This results in “fat overshooting”, which is when you end up with more fat than you had before.

– When we lose fat-free mass (muscles), either due to intentional weight loss or illness, our body responds by increasing our hunger and reducing our energy expenditure. This can lead to weight regain, especially if we lose a lot of fat-free mass. The body tends to store more fat than lean tissue and we end up in worse condition with more fat and fewer muscles. This is called preferential catch-up fat.

– These feedback mechanisms can make it hard to achieve and maintain a healthy weight and muscle mass.

– Dieting can make you more prone to obesity, especially if you start with a normal or low body weight and this was shown in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

– A mathematical model of weight cycling shows that this process can lead to obesity over time, especially in lean individuals. If you keep losing and regaining weight, the amount of fat overshooting will accumulate and eventually outweigh your fat-free mass.

– One thing that the Minnesota Starvation Experiment showed is that our conscious mind is fully unable to escape our evolutionary conditioning and that no matter how strong willpower you might have our reptilian brain usually prevails.

– People will overeat because they can. Any type of dieting will make things even worse in the long run.

The Biology of Human Starvation.

Imagine going hungry for almost half a year. How would that affect your body and mind? That’s what a group of healthy young men volunteered to do in the 1940s, as part of a groundbreaking experiment on the effects of starvation and recovery. The Biology of Human Starvation, published in 1950, is the definitive account of this remarkable study, which has shaped our understanding of how food deprivation impacts human physiology and behavior.

It was one of the first scientific studies on what hunger does to the mind remembered as the Minnesota Starvation Experiment performed by the University of Minnesota back in 1944.

The lead investigator was Ancel Keys who had two Ph.D. one in biology and one from psychology. Thirty-six men were selected that were healthy and had no eating disorders from hundreds who volunteered.

All 36 men agreed to undergo 24 weeks of semi-starvation, followed by 20 weeks of refeeding. During the semi-starvation phase, they were given about 1,600 calories per day, which was about half of their normal intake. They also had to walk several miles daily and perform various physical and mental tasks. During the refeeding phase, they were gradually given more food and different types of diets to see how their bodies and minds recovered.

The experiment was not only a scientific endeavor but also a humanitarian one. It was designed to help the millions of people who were suffering from famine and malnutrition in Europe and Asia after World War II. The researchers hoped to find out how to best treat and rehabilitate them. They also wanted to explore the psychological effects of hunger and starvation on human behavior and personality.

The Biology of Human Starvation is a monumental work that has influenced many fields of research and practice. It has been used as a guide for developing famine and refugee relief programs for international agencies. It has been applied to studying the effects of food deprivation on the cognitive and social functioning of those with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. It has also helped us understand why metabolic adaptations undermine obesity therapy and cachexia rehabilitation.

Summary:

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment, detailed in “The Biology of Human Starvation”, revolutionized our understanding of how food deprivation impacts body and mind, influencing famine relief, eating disorder treatment, and obesity therapy.

Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

Minnesota Starvation Experiment was a study where the goal was to live on a diet of 1600 calories for six months. In the first 12 weeks, there was a 3200-calorie control period, and then a real experiment started.

Now 1600 calories are far from real starvation. The American government wanted to understand what psychological and physiological effects were going to be on war-torn Europe with starvation and the holocaust. There was no industrial or direct military interest in this. It was done as a defense interest project because no one has done anything similar in the past and there was a real concern about the behavior of people that have been exposed to terror and starvation. There was a concern that people who had been released from concentration camps and who had gone through starvation on the battlefront might pose a threat to society. Also, the government wanted to have a guide for rehabilitating those who were starving.

Men were housed in a basement of the Minnesota University Stadium in windowless rooms with a program of mental and physical exercises. Diet was strictly controlled, and they could not cheat because they were in some sense incarcerated for six months.

The scientist initially didn’t think of this experiment as a behavioral experiment in terms of evolutional psychology. The experiment without their initial realization reconstructed the conditions of habitat that existed during the evolution of the human species. An environment of scarcity. Starvation and survival of the fittest. This was an environment that was similar to most of human evolution and as such was more normal than our current environment. It was an environment in which our brain evolved and was designed to cope with. Normal conditions of our current abundance of food were in essence unnatural. The behavior and hunger in an environment of scarcity with a high death rate were the groundwork for understanding what drives our instincts and how strong those instincts are.

On a calorie restriction of 1600 calories after some initial period, subjects started to lose weight and by the end of the study, they lost a significant number of pounds. What was more important is that the experiment did show significant behavioral changes. Starvation did have psychological effects on them.

In the beginning, they started to be apathetic and irritated and they developed ritualized eating patterns. Pouring water into potatoes to make them bigger. Holding the food in the mouth and chewing for an extended period. Licking the plates. Daydreams of food, chewing gum, and smoking cigarettes until someone had 30 packs per day. Drinking a ton of water to fill their stomachs. Then they started to enjoy solitary activities and looked at food in a sexual manner. They had no regular sex drive and were only interested in what people ate. They developed an eating disorder mentality. They started to feel bad about themselves if they binged and felt guilty about food. What they considered normal weight before, during the study was considered to be overweight. When they look at their old pictures, they thought they have big stomachs and much more weight than what will in that situation for them be a normal human physique. They experienced confusion when they are hungry and also when they are not.

This is an extract from one of the volunteer’s diaries:

“I am beginning to isolate myself from other subjects. We are developing all kinds of weird behaviors. Everyone seems to be losing their interpersonal skills and starvation is less than half over. One of them bit the other volunteers. Many tried to escape from the compound to eat grass from nearby gardens. Another became so deranged that he chopped three of his fingers off with an ax.”

Later the ax men stated that he was “messed up” and that he could not remember why or how he chopped his fingers, and he could not say that he did not do it on purpose. This is what a strict diet of 1600 calories did to this person in less than six months.

In cases of hunger, human behavior was shifted to survival mode. Nothing was important except for food. They didn’t care about moral and social norms and didn’t care about sex. They have completely emerged into existentialism that any external input that didn’t have a direct effect on their survival was of less importance to them. Aggressive behavior was avoided only because there was no chance of escaping and because of legal consequences. They were locked in an underground “prison” in the stadium and had very little chance of physically escaping. The scientist predicted this and was strict in subject selection. Before they were chosen to be part of the experiment subjects had to show an ability to get along well with others under trying circumstances and had to have an interest in relief work. They selected nice young men with a good moral compass who had no psychological disorders before the experiment.

Summary:

While mimicking the scarcity of human evolution, the Minnesota Starvation Experiment revealed that even moderate calorie restriction (1600-calorie diet) triggered profound psychological changes like food obsession, isolation, and moral disengagement, highlighting the potent impact of limited resources on human behavior.

What Happened After the Experiment is Even More Important.

When they started to feed on their own wish there was something entirely unexpected.

They rapidly put on weight but not only that. They gained more than what they had at the starting point. Dieting made them fatter. They experienced something called extreme hunger.

They ate and ate and ate and ate and never felt satisfied. Most companies in the diet industry and medical care know about this.

Dieting can make you fatter. Fear of starvation is real. Psychophysical dependence on supernormal stimuli is real. Human beings are evolutionarily conditioned for extreme eating because of the scarcity in nature.

Keys published “The Biology of Human Starvation” in 1950, which describes the impact of long-term food deprivation on human physiology and behavior. The Minnesota Starvation Experiment’s legacy, however, is the impact it has had on research into the effects of food deprivation in those with eating disorders (Keys et al., 1950).

Summary:

Dieters beware! The Minnesota Starvation Experiment revealed a hidden trap: post-starvation “extreme hunger” that makes people gain more weight than they lost initially, challenging dieting wisdom and highlighting the body’s powerful survival mechanisms.

The Results of the Experiment.

The results of the experiment were astonishing and revealing.

They showed that prolonged food deprivation caused significant changes in body composition, metabolism, and appetite regulation. The men lost an average of 25% of their body weight, mostly from muscle and fat tissue.

Their basal metabolic rate (the amount of energy they burned at rest) dropped by about 40%.

Their food intake increased by about 50% during the refeeding phase, but it took them several months to regain their normal weight and body composition. They also experienced various physical and mental symptoms, such as fatigue, weakness, dizziness, edema, hair loss, anemia, depression, anxiety, irritability, apathy, obsession with food, and social withdrawal.

The experiment also revealed some fascinating insights into the complex control systems that regulate body composition during weight loss and weight regain. Using a systems approach to analyze the data on longitudinal changes in body composition, basal metabolic rate, and food intake, the researchers discovered that there was an internal (autoregulatory) control of lean–fat partitioning (highly sensitive to initial adiposity), which operated during weight loss and weight regain.

This means that the body has a mechanism to adjust the proportion of muscle and fat tissue according to its initial state.

They also found that there were feedback loops between changes in body composition and the control of food intake and adaptive thermogenesis (the amount of energy expended above the basal metabolic rate) for the purpose of accelerating the recovery of fat mass and fat-free mass.

This means that the body has a way to communicate with the brain and other organs to regulate hunger–appetite and energy expenditure according to its needs.

Summary:

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment exposed the body’s remarkable ability to adapt to food deprivation (weight loss, lowered metabolism), but also its counterintuitive response to refeeding (extreme hunger, weight regain exceeding initial loss), highlighting complex control systems governing body composition and appetite.

Psychology of Hunger.

Minnesota Starvation Experiment in later years became a base for an understanding of human psychology. Most of the scientists who work for the food industry know about the Minnesota Starvation Experiment very well. It is a well-known fact from that period onward that dieting does not work. After the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, the term “yo-yo” dieting was coined. Everyone who sells diets and supplements, diet plans, and books, all of the scientists in the labs of big food companies knows about this experiment. It was one of the ground-breaking experiments that built a foundation of nutritional science. Food companies, for example, will promote food that is supernormal stimuli (a combination of fat and sugar at the same meal) to the children knowing that once the brain adapts to that stimulation they will be addicted for life.

The way that we are conditioned to behave is the number one avoidance of pain. When pain is avoided pleasure-seeking comes into play. Because of a self-preservation mechanism our brain works by the “carrot and a stick” mechanism. Avoidance of pain is the foundation of individual behavior. Until the pain is removed the pleasure-seeking does not exist and is redundant. People can lose their entire identity and their entire self-controlling mechanisms when forced to be in a state of extreme hunger. We are not in charge.

Psychologists were well aware of this even before the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. But what was a real discovery is that the fear of starvation never, in reality, went away.

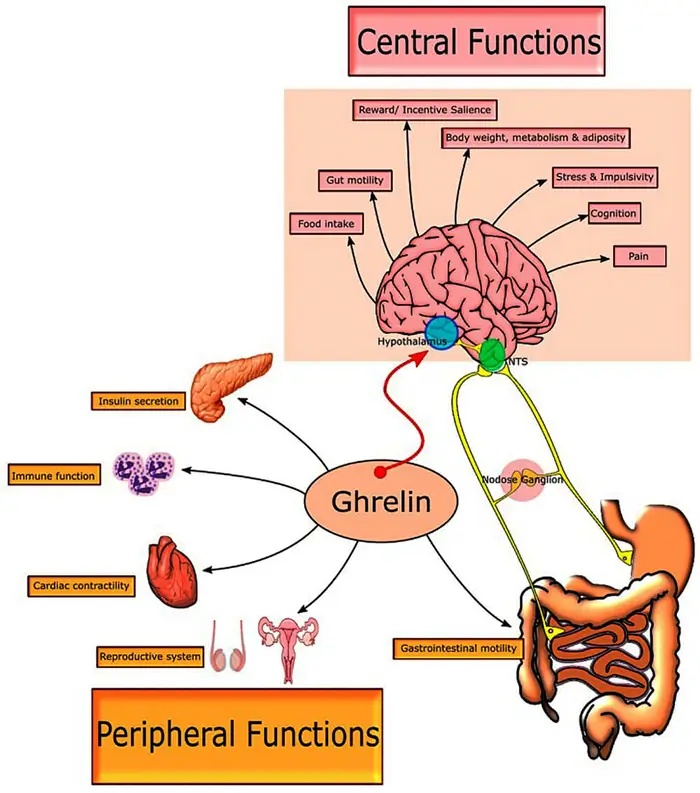

Today there is a wide range of clinical experiments have been done. At the University of Gothenburg in recent years, there was a line of studies but in all cases the conclusion was similar. Ghrelin, the “hunger hormone”, was found for example to directly affect the ventral tegmental area, the part of the brain that is a crucial component of the reward system. Ghrelin injections in rats also caused changes in dopamine-related genes and enzymes (controlling the reward and pleasure centers of the brain) and were also found to make rats more impulsive (Anderberg et al., 2016).

Millions of years of evolution have conditioned our behavior and in a normal natural environment is an evolutionary protective mechanism. In our modern technology-driven environment without scarcity self-controlling mechanisms don’t really work.

Summary:

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment exposed the dark side of dieting, revealing its potential to backfire (yo-yo dieting, extreme hunger) and highlighting how food companies exploit our hunger-driven psychology (supernormal stimuli) to create lifelong customers.

Collateral Fattening.

Have you ever wondered why some people gain more weight than they lost after a period of starvation or dieting? This phenomenon is called “collateral fattening” and it has to do with the role of muscle mass in regulating hunger–appetite and weight.

When you starve yourself or restrict your food intake, you lose not only fat but also muscle. Muscle is an important component of your body composition, as it helps you burn calories and maintain your metabolism. When you lose muscle, your body tries to compensate by increasing your food intake and decreasing your energy expenditure. This is a survival mechanism that helps you restore your muscle mass and prevent further weight loss.

However, restoring muscle mass is not a simple process. It depends on the intrinsic control of lean–fat partitioning, which is highly sensitive to your initial body fat percentage.

This means that the amount of muscle and fat that you regain after starvation or dieting is determined by how much fat you had before. The leaner you were, the more fat you will regain, and the longer it will take to recover your muscle mass. This results in “fat overshooting”, which is when you end up with more fat than you had before.

This phenomenon was observed in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

Summary:

Dieting’s hidden trap: muscle loss during restriction triggers “collateral fattening” where regaining weight prioritizes fat over muscle, leading to exceeding pre-diet weight due to “fat overshooting.”

Management of Obesity and Cachexia.

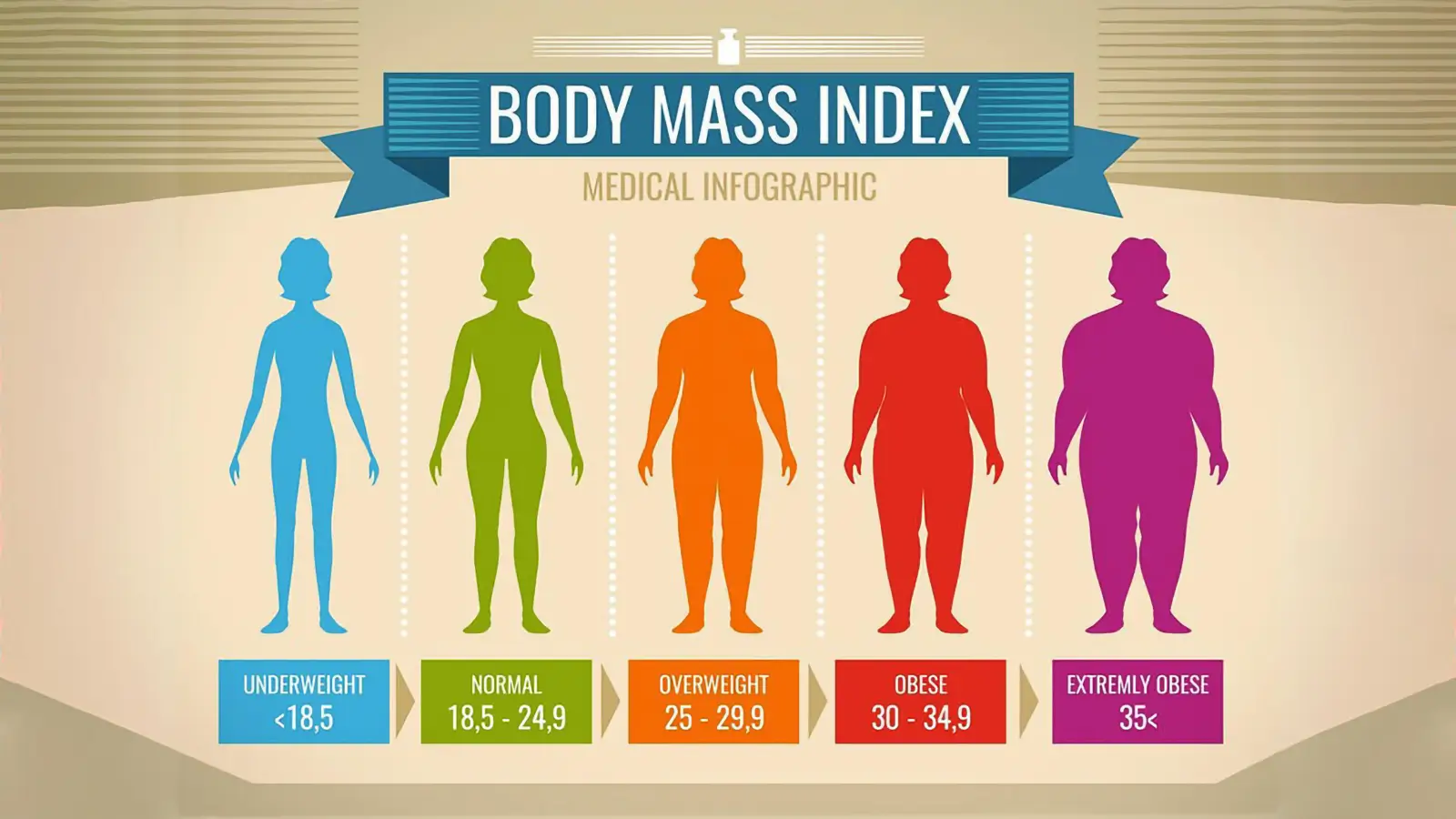

How to manage your weight and muscle mass? Whether you are overweight or underweight, you may have experienced the frustration of losing or gaining fat instead of lean tissue. You may also have noticed that your appetite changes depending on how much fat or muscle you have. Why is that?

The answer lies in the complex feedback loop between your body’s fat stores, energy metabolism, and thermogenesis (the process of heat production). This loop regulates how much energy you burn and how much you eat, and it can affect your body composition in different ways.

One of the key factors in this loop is the adipose-specific control of thermogenesis, which means that your fat cells can influence how much heat you produce. This can have a big impact on your weight and muscle recovery after periods of malnutrition or disease cachexia (a condition that causes severe muscle wasting). When you are recovering from these conditions, your body tends to store more fat than lean tissue, which can impair your health and function. This is called preferential catch-up fat.

Another factor in this loop is the feedback between your fat-free mass (FFM) and your food intake. FFM is the part of your body that is not fat, such as muscles, bones, and organs. When you lose FFM, either due to intentional weight loss or illness, your body responds by increasing your hunger and reducing your energy expenditure. This can lead to weight regain, especially if you lose a lot of FFM.

These feedback mechanisms can make it hard to achieve and maintain a healthy weight and muscle mass. However, there are some strategies that can help you overcome these challenges. Here are some tips:

- If you are overweight or obese, try to lose weight gradually and preserve your FFM as much as possible. This can reduce your hunger and improve your metabolic health. You can do this by following a balanced diet that provides enough protein and essential nutrients, and by doing regular physical activity that includes resistance training.

- If you are underweight or cachectic, try to increase your food intake and stimulate your thermogenesis. This can help you restore your lean tissue and improve your function. You can do this by eating more frequently and choosing foods that are high in calories, protein, and healthy fats. You can also use supplements or medications that boost your appetite and metabolism.

- In both cases, monitor your body composition regularly and adjust your diet and exercise accordingly. You can use tools such as scales, tape measures, calipers, or bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) to measure your weight, body fat percentage, and muscle mass. You can also consult with a health professional who can help you design a personalized plan that suits your needs and goals.

By following these tips, you can manage your weight and muscle mass more effectively and enjoy better health and well-being. Remember that everyone’s body is different, so don’t compare yourself to others or follow unrealistic standards.

Summary:

Whether overweight or underweight, managing your weight and muscle mass requires understanding the complex interplay between fat stores, energy metabolism, and appetite. Focus on gradual, lean-tissue preserving weight loss for overweight individuals, and on boosting appetite and thermogenesis in addition to lean tissue muscle mass bodybuilding for underweight or cachectic individuals.

Dieting and Weight Cycling in the Predisposition to Obesity.

Have you ever tried to lose weight by following a strict diet, only to find yourself gaining more weight later on? If so, you are not alone. Many people experience this frustrating phenomenon, which is known as weight cycling or yo-yo dieting. It happens when you repeatedly lose and regain weight over time, often ending up heavier than before.

You may think that dieting is good for your health and appearance, but it can actually have the opposite effect. Dieting can make you more prone to obesity, especially if you start with a normal or low body weight and this was shown in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

The answer lies in the way your body responds to weight loss and weight regain. When you lose weight, you lose both fat and muscle (also known as fat-free mass or FFM). However, when you regain weight, you tend to gain more fat than muscle. This is called fat overshooting, and it can distort your body composition and metabolism.

Fat overshooting is more likely to happen if you have less body fat, to begin with. This is because when you lose weight, you lose a larger proportion of your FFM and fat mass than someone who has more body fat. This creates a bigger imbalance between your fat and muscle stores, which makes it harder for your body to restore them in sync. As a result, you end up with more fat than before.

A mathematical model of weight cycling shows that this process can lead to obesity over time, especially in lean individuals. If you keep losing and regaining weight, the amount of fat overshooting will accumulate and eventually outweigh your FFM. This can have serious consequences for your health and well-being.

So what can you do to avoid this trap? Here are some tips:

- Don’t diet for the wrong reasons. If you have a normal or low BMI, you don’t need to lose weight for health reasons. Don’t let social pressure, body dissatisfaction, or athletic performance push you to diet unnecessarily.

- Don’t diet too fast or too hard. If you do need to lose weight for medical reasons, do it gradually and moderately. Follow a balanced diet that provides enough calories, protein, and essential nutrients for your body. Avoid very low-calorie diets or extreme fasting that can cause rapid and excessive weight loss.

- Don’t diet alone. Get support from a health professional who can help you design a personalized plan that suits your needs and goals. Monitor your body composition regularly and adjust your plan accordingly. You can use tools such as scales, tape measures, calipers, or bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) to measure your weight, body fat percentage, and muscle mass.

- Don’t give up on physical activity. Exercise is crucial for maintaining your FFM and metabolism. It can also improve your mood, energy, and self-esteem. Do regular physical activity that includes both aerobic and resistance training. Find something that you enjoy and stick with it.

By following these tips, you can break the cycle of dieting and weight gain and achieve a healthy and stable weight and muscle mass.

Summary:

Yo-yo dieting, the frustrating cycle of weight loss and regain, can actually make you gain more fat in the long run due to “fat overshooting,” where your body prioritizes fat storage after muscle loss. This effect is especially pronounced for people with less initial body fat.

FFM Deficit in Predisposition to Obesity.

Being sedentary can make you gain weight and lose muscle, even if you eat the same amount of food as before.

How does this happen? Well, it has to do with the way your body adjusts to different levels of physical activity. When you are active, your body burns calories and builds muscle. Your appetite also matches your energy needs, so you don’t overeat or undereat. This is called energy balance, and it helps you maintain a healthy weight and body composition.

However, when you become sedentary, things change. Your body burns fewer calories and loses muscle mass. Your appetite may not decrease accordingly, so you end up eating more than you need. This is called energy imbalance, and it leads to increased fat storage and weight gain.

But there is more to it than that. Being sedentary can also affect your muscle function and quality. When you don’t use your muscles regularly, they become weaker and smaller. This is called muscle disuse or atrophy, and it can happen in as little as 10 days of bed rest.

This loss of muscle mass can trigger a vicious cycle. According to the concept of collateral fattening, your body tries to restore your muscle mass by increasing your hunger and food intake. However, this may not work, because most of the extra calories you eat go to your fat cells instead of your muscles. So you end up with more fat and less muscle than before.

This cycle can make it hard to achieve and maintain a healthy weight and muscle mass. However, there are some strategies that can help you break it. Here are some tips:

- Don’t be sedentary for too long. Try to move more throughout the day. Get up from your chair every hour or so and walk around. Take the stairs instead of the elevator. Park your car further away from your destination. Find ways to incorporate physical activity into your daily routine.

- Don’t skip exercise. Exercise is essential for preserving your muscle mass and metabolism. It can also improve your mood, energy, and self-esteem. Do regular exercise that includes both aerobic and resistance training. Find something that you enjoy and stick with it.

- Don’t overeat or undereat. Eat a balanced diet that provides enough calories, protein, and essential nutrients for your body. Avoid junk food or processed food that are high in calories but low in nutritional value. Choose whole foods that are rich in fiber, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants.

- Don’t ignore your body signals. Listen to your hunger and fullness cues and eat accordingly. Don’t eat out of boredom, stress, or habit. Drink plenty of water and stay hydrated. Sleep well and avoid caffeine or alcohol before bedtime.

By following these tips, you can avoid the negative effects of being sedentary and improve your weight and muscle management.

Summary:

A sedentary lifestyle leads to muscle loss and a disrupted energy balance, making you gain fat and lose muscle even with unchanged food intake. Then this also triggers a cycle of “collateral fattening” where hunger increases as an attempt to regain muscle through increased eating. This backfires, favoring fat storage instead, and sets off a vicious cycle where regained weight becomes mostly fat, worsening your body composition and potentially pushing you towards obesity.

Body Fat and Muscle Control of Hunger and Metabolism.

Do you ever wonder how your body knows how much to eat and how much energy to burn? It’s not just a matter of calories in and calories out. Your body has a sophisticated system of feedback loops that monitor and regulate your body composition, that is, the amount of fat and muscle you have.

These feedback loops involve sensors and signals that communicate between your fat cells, your muscles, and your brain. They tell your brain how much fat and muscle you have, and how much you need. Based on this information, your brain adjusts your hunger and metabolism accordingly.

For example, when you lose fat, your body tries to restore it by increasing your appetite and lowering your metabolism. This is called the adipostatic system, and it helps you maintain a stable level of body fat. On the other hand, when you lose muscle, your body tries to rebuild it by increasing your hunger and boosting your metabolism. This is called the proteinstatic system, and it helps you preserve your muscle mass.

These systems are important for your health and well-being. They help you adapt to different situations, such as starvation, overfeeding, illness, or exercise. They also help you prevent or recover from obesity, malnutrition, or cachexia (a condition that causes severe muscle wasting).

However, these systems are not fully understood. There are many gaps in knowledge about how they work and what factors influence them. For instance, we don’t know exactly what sensors and signals are involved in these systems. We know that leptin, a hormone secreted by fat cells, plays a role in the adipostatic system, but it’s not the only factor. There are other unknown factors that affect how your body responds to changes in body fat. Similarly, we don’t know what sensors and signals are involved in the proteinstatic system. We don’t know what part of your muscle mass is being sensed and how it affects your hunger and metabolism. We also don’t know how your fat cells and muscles interact with each other to regulate your thermogenesis (the process of heat production).

Summary:

Our body’s intricate fat and muscle feedback loops, while vital for maintaining stability, remain shrouded in mystery, influencing hunger, metabolism, and responses to conditions like obesity and muscle wasting. These sophisticated body feedback loops adjust hunger and metabolism to maintain stable fat and muscle levels.

How Our Body Adapts to Hunger. Summary.

Imagine living in a world where food is scarce and unpredictable. You never know when you will find your next meal, or how long it will last. You have to survive on whatever you can get, even if it means going hungry for days or weeks. How would your body cope with this situation?

This is the kind of world that our ancestors faced for millions of years. They had to deal with frequent periods of famine and food shortages, which threatened their survival and reproduction. To overcome this challenge, they developed a remarkable ability to adjust their body weight and composition according to the availability of food. This ability is called body composition autoregulation, and it involves a complex system of feedback loops that control your hunger, metabolism, and fat and muscle storage.

These feedback loops help you adapt to different phases of energy balance. When you are in a negative energy balance, meaning that you are burning more calories than you are eating, your body tries to conserve energy and protect your vital organs. It does this by reducing your appetite, slowing down your metabolism, and breaking down your fat and muscle tissue. This is called the famine reaction, and it helps you survive longer without food.

However, when you are in a positive energy balance, meaning that you are eating more calories than you are burning, your body tries to restore its normal function and prepare for the next famine. It does this by increasing your appetite, speeding up your metabolism, and rebuilding your fat and muscle tissue. This is called the recovery reaction, and it helps you regain your health and fitness.

These reactions are important for your well-being. They help you adapt to changing environments and cope with stressors. They also help you maintain a stable level of body fat and muscle mass that is optimal for your survival and reproduction.

However, these reactions can also cause problems in the modern world. Today, we live in a world where food is abundant and easily accessible. We rarely face periods of famine or food shortages. Instead, we face the opposite problem: overeating and obesity. This can disrupt the feedback loops that regulate our body composition and cause us to gain more weight and lose more muscle than we need.

This can also affect our response to weight loss interventions or disease treatments that involve changes in our energy intake or expenditure. For example, when we try to lose weight by dieting or exercising, our body may react as if we are in a famine situation and activate the famine reaction. This can make us feel hungrier, burn fewer calories, and lose more muscle than fat. This can make it harder to achieve and maintain our weight loss goals.

Similarly, when we suffer from a disease that causes muscle wasting or cachexia (such as cancer or AIDS), our body may react as if we are in a recovery situation and activate the recovery reaction. This can make us eat more, burn more calories, and gain more fat than muscle. This can make it harder to recover our muscle mass and function.

These problems are not easy to solve. These are some of the questions that scientists are trying to answer. They are using data from experiments such as the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. They are also using new methods such as genomics, proteinomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics to identify the hundreds of factors that are secreted by our fat cells and muscles.

One thing that Minnesota Starvation Experiment showed is that our conscious mind is fully unable to escape our evolutionary conditioning and that no matter how strong willpower you might have our reptilian brain usually prevails.

I always like to give a comparison with drowning. If we want to commit suicide by holding our breath, for example, we will not be able to. Sooner or later our brain will override our behavior and will gasp for air. It detects pain and it is in a state of dying one way or the other so there is nothing to lose anyway. This is a reason people always drown and do not suffocate. The same story is with food or water.

Summary:

People will overeat because they can. Any type of dieting will make things even worse in the long run.

Even if we try to lose weight we are going to be in a constant struggle against our conditioning. And even if we do prevail, it is not possible to be in a state of hunger and enjoy life. Especially because now we are removed from our natural environment and we have supernormal stimuli everywhere. Even a normal feeling of hunger is something that we cannot take as a normal feeling anymore.

FAQ

References:

- Anderberg, R. H., Hansson, C., Fenander, M., Richard, J. E., Dickson, S. L., Nissbrandt, H., Bergquist, F., & Skibicka, K. P. (2016). The Stomach-Derived Hormone Ghrelin Increases Impulsive Behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(5), 1199–1209. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.297

- Kalm, L. M., & Semba, R. D. (2005). They starved so that others be better fed: remembering Ancel Keys and the Minnesota experiment. The Journal of nutrition, 135(6), 1347–1352. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/135.6.1347

- Tobey J. A. (1951). The Biology of Human Starvation. American Journal of Public Health and the Nations Health, 41(2), 236–237.[PubMed]

- Howick, K., Griffin, B. T., Cryan, J. F., & Schellekens, H. (2017). From Belly to Brain: Targeting the Ghrelin Receptor in Appetite and Food Intake Regulation. International journal of molecular sciences, 18(2), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020273

- Müller, M. J., Enderle, J., Pourhassan, M., Braun, W., Eggeling, B., Lagerpusch, M., Glüer, C. C., Kehayias, J. J., Kiosz, D., & Bosy-Westphal, A. (2015). Metabolic adaptation to caloric restriction and subsequent refeeding: the Minnesota Starvation Experiment revisited. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 102(4), 807–819. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.109173

- Dulloo A. G. (2021). Physiology of weight regain: Lessons from the classic Minnesota Starvation Experiment on human body composition regulation. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 22 Suppl 2, e13189. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13189

- LASKER G. W. (1947). The effects of partial starvation on somatotype: an analysis of material from the Minnesota starving experiment. American journal of physical anthropology, 5(3), 323–341. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330050305

- Dulloo, A. G., Jacquet, J., & Girardier, L. (1996). Autoregulation of body composition during weight recovery in human: the Minnesota Experiment revisited. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 20(5), 393–405.[PubMed]

- Keys et al. (1950) “The Biology of Human Starvation (2 volumes)”. University of Minnesota Press.

- Dulloo, A. G. Physiology of weight regain: Lessons from the classic Minnesota Starvation Experiment on human body composition regulation. Obesity Reviews, 22, e13189. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13189

Do you have any questions about nutrition and health?

I would love to hear from you and answer them in my next post. I appreciate your input and opinion and I look forward to hearing from you soon. I also invite you to follow us on Facebook, Instagram, and Pinterest for more diet, nutrition, and health content. You can leave a comment there and connect with other health enthusiasts, share your tips and experiences, and get support and encouragement from our team and community.

I hope that this post was informative and enjoyable for you and that you are prepared to apply the insights you learned. If you found this post helpful, please share it with your friends and family who might also benefit from it. You never know who might need some guidance and support on their health journey.

– You Might Also Like –

Learn About Nutrition

Milos Pokimica is a doctor of natural medicine, clinical nutritionist, medical health and nutrition writer, and nutritional science advisor. Author of the book series Go Vegan? Review of Science, he also operates the natural health website GoVeganWay.com

Medical Disclaimer

GoVeganWay.com brings you reviews of the latest nutrition and health-related research. The information provided represents the personal opinion of the author and is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The information provided is for informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as a substitute for the consultation, diagnosis, and/or medical treatment of a qualified physician or healthcare provider.NEVER DISREGARD PROFESSIONAL MEDICAL ADVICE OR DELAY SEEKING MEDICAL TREATMENT BECAUSE OF SOMETHING YOU HAVE READ ON OR ACCESSED THROUGH GoVeganWay.com

NEVER APPLY ANY LIFESTYLE CHANGES OR ANY CHANGES AT ALL AS A CONSEQUENCE OF SOMETHING YOU HAVE READ IN GoVeganWay.com BEFORE CONSULTING LICENCED MEDICAL PRACTITIONER.

In the event of a medical emergency, call a doctor or 911 immediately. GoVeganWay.com does not recommend or endorse any specific groups, organizations, tests, physicians, products, procedures, opinions, or other information that may be mentioned inside.

Editor Picks –

Milos Pokimica is a health and nutrition writer and nutritional science advisor. Author of the book series Go Vegan? Review of Science, he also operates the natural health website GoVeganWay.com

Latest Articles –

Top Health News — ScienceDaily

- The overlooked nutrition risk of Ozempic and Wegovyon February 4, 2026

Popular weight-loss drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy can dramatically curb appetite, but experts warn many users are flying blind when it comes to nutrition. New research suggests people taking these medications may not be getting enough guidance on protein, vitamins, and overall diet quality, increasing the risk of muscle loss and nutrient deficiencies.

- A 25-year study found an unexpected link between cheese and dementiaon February 4, 2026

A massive Swedish study tracking nearly 28,000 people for 25 years found an unexpected link between full-fat dairy and brain health. Among adults without a genetic risk for Alzheimer’s, eating more full-fat cheese was associated with a noticeably lower risk of developing the disease, while higher cream intake was tied to reduced dementia risk overall. The findings challenge decades of low-fat dietary advice but come with important caveats.

- MIT’s new brain tool could finally explain consciousnesson February 4, 2026

Scientists still don’t know how the brain turns physical activity into thoughts, feelings, and awareness—but a powerful new tool may help crack the mystery. Researchers at MIT are exploring transcranial focused ultrasound, a noninvasive technology that can precisely stimulate deep regions of the brain that were previously off-limits. In a new “roadmap” paper, they explain how this method could finally let scientists test cause-and-effect in consciousness research, not just observe […]

- Why heart disease risk in type 2 diabetes looks different for men and womenon February 4, 2026

Scientists are digging into why heart disease risk in type 2 diabetes differs between men and women—and sex hormones may be part of the story. In a large Johns Hopkins study, men with higher testosterone had lower heart disease risk, while rising estradiol levels were linked to higher risk. These hormone effects were not seen in women. The results point toward more personalized approaches to heart disease prevention in diabetes.

- Sound machines might be making your sleep worseon February 4, 2026

Sound machines may not be the sleep saviors many believe. Researchers found that pink noise significantly reduced REM sleep, while simple earplugs did a better job protecting deep, restorative sleep from traffic noise. When pink noise was combined with outside noise, sleep quality dropped even further. The results suggest that popular “sleep sounds” could be doing more harm than good—particularly for kids.

- This unexpected plant discovery could change how drugs are madeon February 3, 2026

Plants make chemical weapons to protect themselves, and many of these compounds have become vital to human medicine. Researchers found that one powerful plant chemical is produced using a gene that looks surprisingly bacterial. This suggests plants reuse microbial tools to invent new chemistry. The insight could help scientists discover new drugs and produce them more sustainably.

- A hidden cellular process may drive aging and diseaseon February 3, 2026

As we age, our cells don’t just wear down—they reorganize. Researchers found that cells actively remodel a key structure called the endoplasmic reticulum, reducing protein-producing regions while preserving fat-related ones. This process, driven by ER-phagy, is tied to lifespan and healthy aging. Because these changes happen early, they could help trigger later disease—or offer a chance to stop it.

PubMed, #vegan-diet –

- Diet type and the oral microbiomeon February 2, 2026

CONCLUSION: The diet-oral microbiome-systemic inflammation axis is bidirectional and clinically relevant. Understanding both direct ecological regulation and indirect metabolic effects is essential to support precision nutrition strategies aimed at maintaining oral microbial balance and systemic inflammatory risk mitigation.

- Consensus document on healthy lifestyleson January 22, 2026

Proteins are a group of macronutrients that are vital to our lives, as they perform various functions, including structural, defensive and catalytic. An intake of 1.0-1.2 g/kg/body weight per day would be sufficient to meet our needs. Carbohydrate requirements constitute 50 % of the total caloric value and should be obtained mainly in the form of complex carbohydrates. In addition, a daily intake of both soluble and insoluble fiber is necessary. Regular consumption of extra virgin olive oil […]

- Vitamin B12 and D status in long-term vegetarians: Impact of diet duration and subtypes in Beijing, Chinaon January 21, 2026

CONCLUSIONS: This study reveals a dual challenge among Beijing long-term vegetarians: vitamin B12 deficiency was strongly associated with the degree of exclusion of animal products from the diet (veganism), while vitamin D deficiency was highly prevalent and worsened with longer diet duration. The near-universal vitamin D deficiency observed in this study suggests that, in the Beijing context, the risk may extend beyond dietary choice, potentially reflecting regional environmental factors;…

- Nutritional evaluation of duty meals provided to riot police forces in Germanyon January 13, 2026

Background: The primary role of the German riot police is maintaining internal security. Due to challenging working conditions, riot police forces face an elevated risk of various diseases. During duty, forces are provided with meals. A balanced diet can reduce the risk of some of these diseases and contribute to health-promoting working conditions. Aim: First evaluation of the nutritional quality of duty meals in Germany based on German Nutrition Society recommendations (DGE). Methods: In…

- Iodineon January 1, 2006

Iodine is an essential trace nutrient for all infants that is a normal component of breastmilk. Infant requirements are estimated to be 15 mcg/kg daily in full-term infants and 30 mcg/kg daily in preterm infants.[1] Breastmilk iodine concentration correlates well with maternal urinary iodine concentration and may be a useful index of iodine sufficiency in infants under 2 years of age, but there is no clear agreement on a value that indicates iodine sufficiency, and may not correlate with […]

Random Posts –

Featured Posts –

Latest from PubMed, #plant-based diet –

- From paddy soil to dining table: biological biofortification of rice with zincby Lei Huang on February 4, 2026

One-third of paddy soils are globally deficient in zinc (Zn) and 40% of Zn loss in the procession from brown rice to polished rice, which results in the global issue of hidden hunger, e.g., the micronutrient deficiencies in the rice-based population of developing countries. In the recent decades, biofortification of cereal food crops with Zn has emerged as a promising solution. Herein, we comprehensively reviewed the entire process of Zn in paddy soil to human diet, including the regulatory…

- Molecular Characterization of Tobacco Necrosis Virus A Variants Identified in Sugarbeet Rootsby Alyssa Flobinus on February 3, 2026

Sugarbeet provides an important source of sucrose; a stable, environmentally safe, and low-cost staple in the human diet. Viral diseases arising in sugarbeet ultimately impact sugar content, which translates to financial losses for growers. To manage diseases and prevent such losses from occurring, it is essential to characterize viruses responsible for disease. Recently, our laboratory identified a tobacco necrosis virus A variant named Beta vulgaris alphanecrovirus 1 (BvANV-1) in sugarbeet…

- Nutrition in early life interacts with genetic risk to influence preadult behaviour in the Raine Studyby Lars Meinertz Byg on February 3, 2026

CONCLUSIONS: Nutrition in early life and psychiatric genetic risk may interact to determine lasting child behaviour. Contrary to our hypothesis, we find dietary benefits in individuals with lower ADHD PGS, necessitating replication. We also highlight the possibility of including genetics in early nutrition intervention trials for causal inference.

- Effect of the gut microbiota on insect reproduction: mechanisms and biotechnological prospectsby Dilawar Abbas on February 2, 2026

The insect gut microbiota functions as a multifunctional symbiotic system that plays a central role in host reproduction. Through the production of bioactive metabolites, gut microbes interact with host hormonal pathways, immune signaling, and molecular regulatory networks, thereby shaping reproductive physiology and fitness. This review summarizes recent advances in understanding how gut microbiota regulate insect reproduction. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that microbial metabolites…

- Rationale and design of a parallel randomised trial of a plant-based intensive lifestyle intervention for diabetes remission: The REmission of diabetes using a PlAnt-based weight loss InteRvention…by Brighid McKay on February 2, 2026

CONCLUSIONS: This trial will provide high-quality clinical evidence on the use of plant-based ILIs to address the epidemics of obesity and diabetes to inform public health policies and programs in Canada and beyond.

- Diet type and the oral microbiomeby Daniel Betancur on February 2, 2026

CONCLUSION: The diet-oral microbiome-systemic inflammation axis is bidirectional and clinically relevant. Understanding both direct ecological regulation and indirect metabolic effects is essential to support precision nutrition strategies aimed at maintaining oral microbial balance and systemic inflammatory risk mitigation.